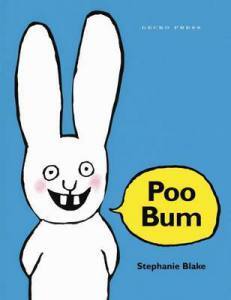

Born in 1968 in Northfield, Minnesota, Stephanie Blake settled in Paris and began writing for children. She is a self-taught author and illustrator, whose favourite authors include AA Milne, Astrid Lindgren, Doctor Seuss and Tomi Ungerer, and nursery rhymes. It is 20 years since the original edition of Blake’s Poo Bum was published in France. Since then, she has published 40 books for children. The Simon books have sold 4.5 million copies worldwide and been translated into 19 languages. Gecko Press released the English edition of Poo Bum in 2011 and it has sold over 80,000 copies in English. The Simon animated series is on Netflix worldwide along with local releases in 30 countries.

Born in 1968 in Northfield, Minnesota, Stephanie Blake settled in Paris and began writing for children. She is a self-taught author and illustrator, whose favourite authors include AA Milne, Astrid Lindgren, Doctor Seuss and Tomi Ungerer, and nursery rhymes. It is 20 years since the original edition of Blake’s Poo Bum was published in France. Since then, she has published 40 books for children. The Simon books have sold 4.5 million copies worldwide and been translated into 19 languages. Gecko Press released the English edition of Poo Bum in 2011 and it has sold over 80,000 copies in English. The Simon animated series is on Netflix worldwide along with local releases in 30 countries.

What led you to create Simon’s world?

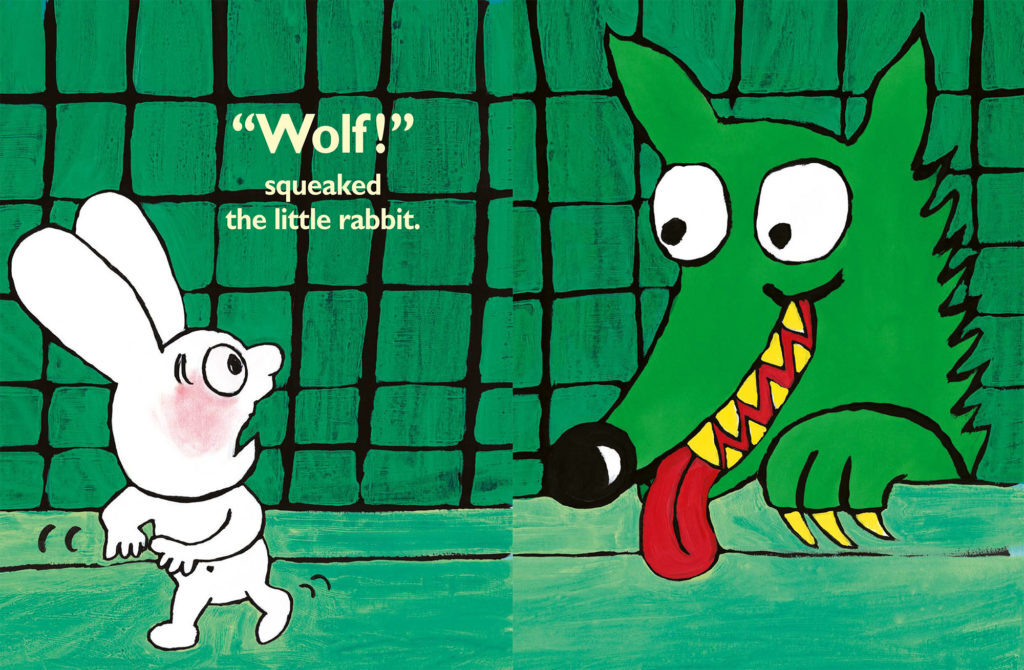

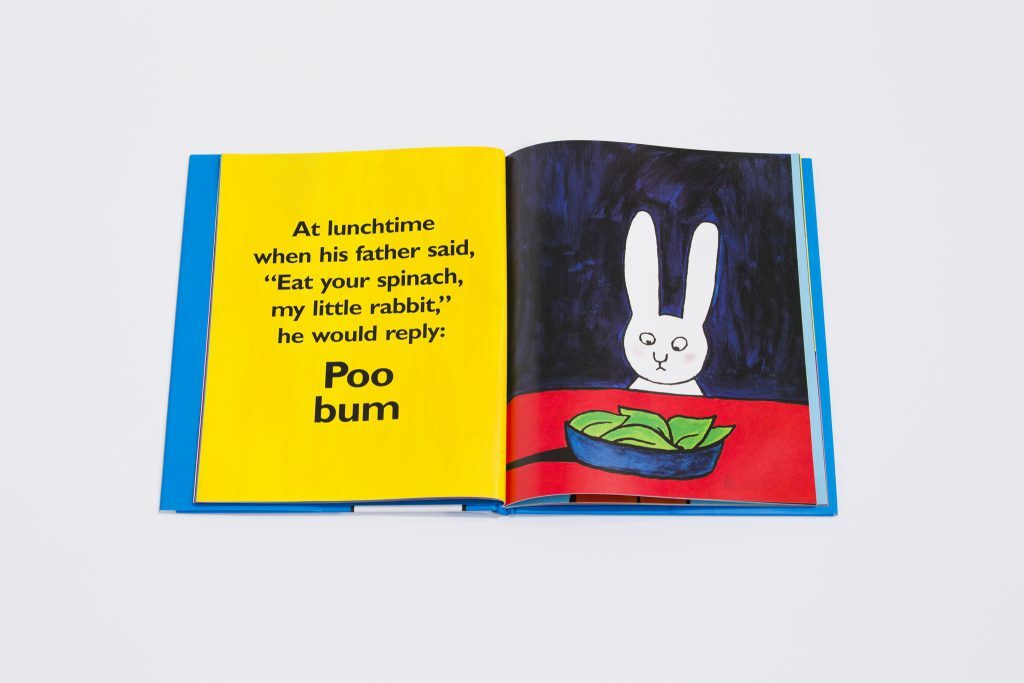

In 2002, I wrote Caca Boudin [Poo Bum]. I’d already written and illustrated 20 books featuring a range of characters, inspired by various authors. With Caca Boudin [Poo Bum], I found my way of writing – my tone, my music – and Simon. Once I had Simon, everything clicked, and I was no longer working with the abstract idea of writing a book or making beautiful images. Books became my second language and Simon an extension of myself. I had a new freedom to play with words and images. I allowed myself to write the way I wanted to.

How do you keep Simon’s stories fresh when they talk about everyday subjects?

Even though there’s a consistent structure to these picture books – Simon has a problem, the problem gets unbearable, and Simon has to find a solution – that’s the only constant in these stories. I don’t write about the everyday. I write about life, or more precisely, about life’s transitions and the emotions they generate. These emotions are universal: joy, happiness, love, injustice, challenging and improving yourself, loss of a loved one, all the things that our life is made of. We all go through them and so do children.

Why do you think your stories resonate so much for children?

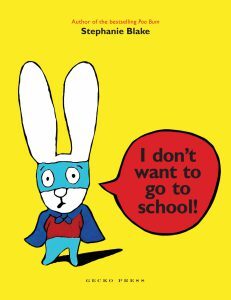

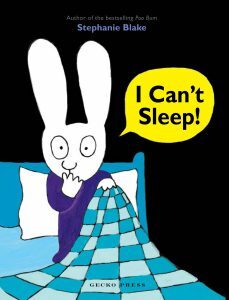

I speak to children, not adults, so when I write, I step aside from being an adult and adjust my own feelings and experiences to those of a child. For example, if in my life as an adult I have to overcome a difficulty, I transpose what I feel: frustration, fear, humour, humiliation or other feelings. If I’m feeling nervous about starting a new job and can’t sleep – I’m afraid of the unknown, afraid I won’t get it, I’d rather stay at home – but I have to push myself. When does a child feel the same as me? The first day of school, perhaps. There’s the same anxiety, the same fear of the unknown, exactly the same feelings as mine. So I transfer those emotions to a child’s world by writing about a first day of school, rather than my new job. This creates following structure:

1. Tomorrow is the first day of school.

2. Simon is anxious and can’t sleep.

3. He panics and refuses to go.

4. He overcomes his fear and goes to school.

5. Finally, he is happy at school and doesn’t want to go home.

I try not to take everyday life too seriously, but not only to be in the child’s world; it’s also how I live in my life. I also try to be self-aware and mock myself from time to time. This allows me to put things into perspective and take a step back.

Your graphic universe is very recognizable: how did you build and evolve it? What are your sources of inspiration?

Your graphic universe is very recognizable: how did you build and evolve it? What are your sources of inspiration?

I was inspired by my favourite authors. Graphically, I was most inspired by the world of Tomi Ungerer. When I started to write and illustrate stories, solid colours and black lines were in fashion. I haven’t invented anything.

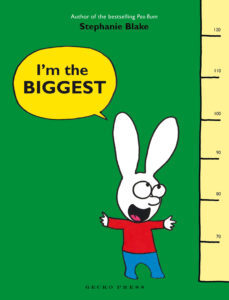

But what is very personal is my colour palette. I like bold, strong colours – they’re like me. I’m a bit brusque and direct, even with children. I don’t do softness, and my colours are not soft either. I’ve tried pastel shades for a change, but I feel like I’m losing my strength and identity. I use primary colours to get straight to the point of what Simon is going through and feeling. I love conveying emotions through his expressions. I have a lot of fun drawing.

As a child, you created stories for your brothers and sisters. Are you thinking of giving Simon more siblings as a tribute to your own?

I tried to in my book Mais…c’est pas moi ! In this story, Simon and Casper have a little sister. I was inspired by my own life. My sons Louis and Jean had just got a little sister, Scarlett. Suddenly Jean, my youngest, found himself the middle child. I wanted to tell the story of this change of place in the family.

I thought I’d be able to slowly grow Simon’s family like my own, but I soon realised that when I wrote a story with Suzanne as the main character, Simon would get lost. And Simon is my bridge to children, Simon is my hero.

This book made me realise that all the other characters who revolve around Simon are actually his sidekicks. Little brother Casper, girlfriend Lou, Ferdinand the best friend/enemy and the cat – they let me keep Simon at the centre of the story. Simon becomes Casper’s hero, Lou helps Simon to think and to make his wish come true. Ferdinand has a bit of a bad guy role – when I need a negative character to counter Simon, he’s the one who does it. All of this used to be unconscious, but the arrival of a little sister made me realise that I risked losing my thread and my hero if I had too many characters.

I make a few exceptions. Non Pas Le Pot is really a book about Casper because he allows me to talk to toddlers. I can have a wide range of stories because I sometimes write about problems that are more those of a 6–7-year-old, for example Top-là!, Nultiplication or Donner c’est donner [A Deal’s a Deal]. In my latest book, I’ve given myself the freedom to make Lou my main character. But it’s an exception, a spin-off, in a way.

Did you expect to be so successful?

Did you expect to be so successful?

Simon came along at just the right time. Without him I probably wouldn’t have been able to continue writing, but with Simon I started to make a living from my work. Although I never thought I would be so successful, or knew whether a book would work or not, I always knew I wanted to write for children. Still today, while I have a lot of different creative projects, Simon remains my reference point, my foundation. I didn’t end up writing books by default; I chose this.

What have you learnt from becoming an established children’s writer?

I have a lot of fun writing. Things are easier nowadays, because I have an established career and I now know when a story is worthwhile or not. When I was younger, I used to give my all to a book without knowing the difference. I worked hard and thought that the sincerity of what I was writing and the time I spent doing it (sometimes day and night!) was a kind of guarantee of the final result. And when my work was rejected, I would be outraged and thought the publisher had misunderstood my work.

I also needed to pay my rent and live off my work, so it was significant financially when a book was rejected after spending months on it. But I think that’s the only way to understand that if you want to make a living out of writing, you have to make it work. Or else you have to work as a waiter on the side. The publisher could be wrong, of course. But I know that often if a writer’s (sometimes unconscious) motivation is wrong – more focused on paying the rent, writing a beautiful book and being recognised or just having fun with their love of drawing – it won’t necessarily result in the best children’s story. It’s complicated, and I say this without pretension because being a writer is not a very well regarded profession in France, even though it’s a wonderful job.

What do you still find challenging about writing?

The hardest thing is knowing what you want to say. A good publisher must always ask the author this simple question, because it can sometimes be forgotten in a beautiful image or a story that we think is original or relevant. It all comes back to what do you want to say? This question is the same whether I am working on a sculpture, a canvas or a video.

What have children said to you about Simon?

It was comments from children that got me back in the saddle when I thought I had run out of ideas.

Shortly after Caca Boudin [Poo Bum] was published, I was invited to a tiny kindergarten deep in the countryside in the Perche region. It was 8.25 am, and I was waiting for the children to arrive while drinking coffee in front of the school. At 8:30 am, a small blue bus parked in front of me. The doors opened and twenty little children wearing white paper rabbit ears got off. They lined up and entered the school in silence. I was overwhelmed with emotion; they were so cute!

I went inside and stood on the stage to start the workshop, and a little girl wearing rabbit ears raised her hand and asked, ‘Where’s Simon’s mum?’ I introduced myself. ‘It’s me, I’m Stephanie Blake, I created Simon…’ ‘But you’re not a rabbit!’ And they all burst into tears! Simon was so real to them, and that’s when I realised he was the bridge between them and me. He’s not just a little white rabbit who challenges parental authority; he really exists for children. From then on, he started to really exist for me.

Not long afterwards, I had just read Caca Boudin [Poo Bum] to another group and a child asked, ‘What’s he going to do next?’ I asked, ‘Who?’ The child replied, ‘Simon of course.’

What’s Simon going to do next? The question stayed with me when I was on the train back to Paris that evening.

During a session with a class at a Canadian Book Fair, a little boy came up and asked me if he could touch me. ‘Yes! Of course! But why?’ I replied. ‘To find out if you are real!’

Magic! I got back on the plane with ideas just for him!

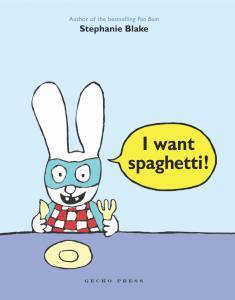

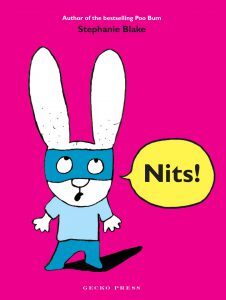

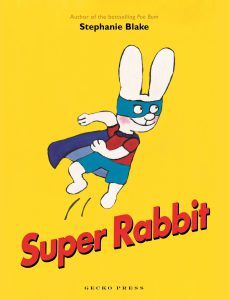

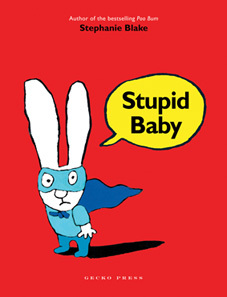

Poo Bum and other books in the series about Simon the Rabbit are available from your local bookstore or on our website.