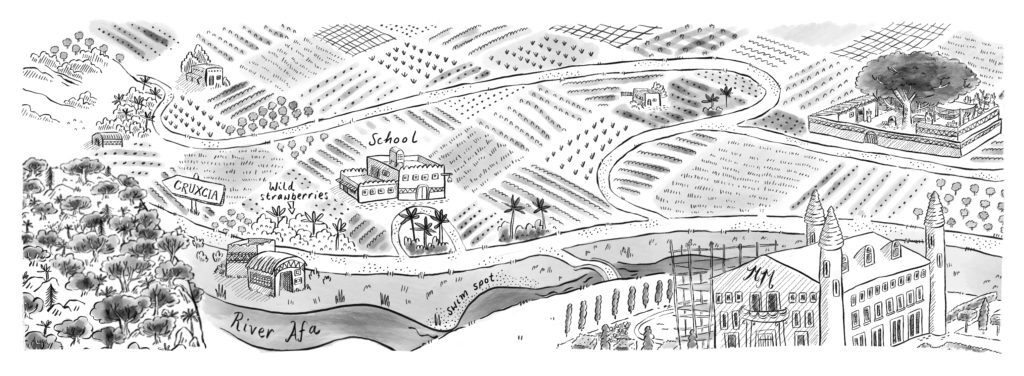

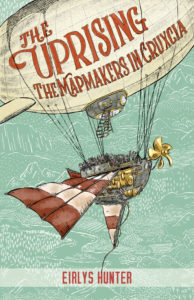

On the release of her ninth children’s novel, follow-up to The Mapmakers’ Race, Eirlys Hunter talks about the kind of books she likes to write, and ideas of fantasy and reality in children’s books.

I don’t think of the Mapmakers books as fantasy in any traditional sense. There is some invented technology but nothing that couldn’t actually exist in the real world. Everything in the stories obeys all physical and natural laws; there are no dragons, there is no magic. No one can freeze time or turn straw into gold. There’s only one element that’s impossible, and that is that one character can fly. Or, more accurately, she can rise up above her body, lying on the ground, and see the landscape from above. We can see the landscape from above too of course, but we use Google Earth.

What is ‘the real world’?

The Shorter Oxford Dictionary defines fantasy as a literary genre in which the plot could not occur in the real world. Let’s think about some plots from children’s books. Which plots could not occur in the real world? How about a story in which four siblings aged seven, eight, ten and twelve, from a caring (not neglectful) family are allowed to spend their holidays camping on an island in the middle of a deep lake, cooking their own food, sailing around, no adults checking up on them, and no life jackets. The seven-year-old can’t even swim. But nobody thought their parents irresponsible. No one called the Windermere branch of the Child Protection Agency.

Or how about a novel set in in pre-revolutionary Russia, in which a child works to re-wild wolves that have become too large and too fierce to be fashionable pets, and then goes on a quest with her wolves through the deep snow of the winter forest, while being chased by soldiers, to start a revolution and rescue her mother from jail? Reality or fantasy?

Or what about the novels that involve around such unfamiliar concepts as prom queens, grade point averages, going on dates, drinking Dr Peppers and eating Graham crackers?

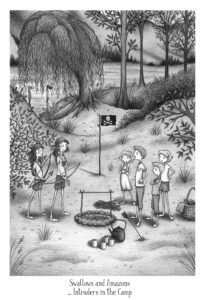

All of these plots are set in ‘the real world’, although they are not real worlds that most young readers in Aotearoa would recognise. Swallows and Amazons was published in 1930 and expectations of children and parenting must have been very different then. Arthur Ransome’s books belong to another era. Let’s call it the Fantasy of Time.

Katherine Rundell’s The Wolf Wilder (2015) is an original and exciting historical novel, and moment by moment nothing impossible happens (no wizards, no dragons), but the whole story is fantastical. It’s not of here and now, and actually wolf wilders were never a real thing, but she’s such a good story-teller that I have no difficulty believing it could have happened over there, back then.

And those American novels of the 1980s and 1990s (Paula Danziger, Judy Blume) were, according to my eldest daughter who read them by the armful when she was eleven or twelve, so alien, and so far from her own school experience, that they might as well have been set in Hogwarts. This is the same feeling that Margaret Mahy had as a child when the books she read seemed to be set in another world – the world of snow at Christmas and woods full of squirrels and foxes. Let’s call it the Fantasy of Place.

Magic and realism

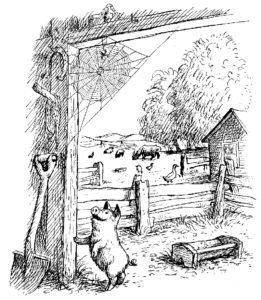

I’d argue that most novels for pre-adolescent children are fantasy of one kind or another because the worlds and lives they depict have little in common with most children’s experience. Indeed, some stories that contain elements of magic seem a lot more believable than ones that are set in ‘the real world.’ Take two books I loved as a child. One is a story set on a farm with a real, familiar-seeming family where the animals talk to each other and a spider spins words into her web. In the other, a rich girl in a Victorian boarding school is forced into servitude when her father dies and her fees are unpaid – but someone creeps over the rooftops and through her skylight to leave food and luxuries for her in her attic garret, until she is ultimately restored to wealth and her rightful position in society.

By the Shorter Oxford’s definition, Charlotte’s Web is fantasy and The Little Princess is not, but the Cinderella-y, riches-to rags-to riches story of Sara Crewe in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s novel feels more fantastical than the fable of the spider who makes Wilbur the pig famous in EB White’s. Both these stories felt equally true to me as a child. I spent quite a lot of time being Sara Crewe, and her attic transformations didn’t seem any more or less real than when, for instance, I was being Lucy in CS Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and became a queen. (And like many bookish children I never went past a wardrobe without testing whether the back was solid. Of course, I knew Narnia was a fantasy on one level, but that didn’t stop me hoping, as I pushed aside old mothballed clothes, that this time I’d find myself out of boring reality, and into Lantern Waste).

Children don’t experience a concrete division between reality and fantasy as adults do, for a number of reasons. Firstly, children are still exploring the limits of reality. Something that’s not real now might have been real once (after all, dinosaurs used to roam the earth), or might be real somewhere else, on the other side of this enormous planet.

And can magic be real? The American children’s writer Katherine Paterson talks about the child’s eye that sits at the heart of any good story for children, and reminds us that that eye constantly experiences wonder. And the wonder of the natural world, when newly encountered, is very close to, maybe even indistinguishable from, magic. For a city child who sees the ocean for the first time, or who realises that a tiny spider has spun that huge and complex web across the porch, or who watches a caterpillar turn into a green and gold chrysalis, then hatch into a monarch butterfly – aren’t they watching something magical? Magic is all around children, and the difference between those things that can and those things that can’t happen in the real world doesn’t become clearer until adolescence – if then.

The boundary between the real and the imagined

But the main reason why children find the boundary between real and imagined fluid – or perhaps irrelevant – is because pre-teen children spend much of their waking life being someone, or something, else. Whether from books or TV programmes, the stories children know spill out into their lives and become part of the fabric of their experience.

But the main reason why children find the boundary between real and imagined fluid – or perhaps irrelevant – is because pre-teen children spend much of their waking life being someone, or something, else. Whether from books or TV programmes, the stories children know spill out into their lives and become part of the fabric of their experience.

I wonder if one of the reasons that Swallows and Amazons has remained popular through four generations is because Ransome’s child characters’ fantasy life is so central to the books. On the first page Roger is seen running up the field to his mother in long shallow zig-zags. He isn’t trying to get there as slowly as possible, he’s tacking against the wind, because he isn’t a boy at that moment, he’s being a sailing vessel, the Cutty Sark. The stories and poems that the Walker and Blackett children know inform the way they play, but, as they are allowed to spend days without adults, the stories – Robinson Crusoe, Treasure Island – become part of everything that they do. The children are allowed to live their stories and play their lives. Fantasy and reality are inseparable.

The books I loved as a child were adventure stories. Books in which children crossed Europe on foot, hid from Roundheads, rode horses across moors at night, put on plays, solved crimes and escaped from evil people. Sometimes they were at boarding school, but even if they weren’t, parents seldom featured. There may have been the occasional permeable wardrobe, time slip or Psammead in the stories I read and reread but to me that magical element was only important because it provided a portal to the action. And crucially, action in which children operated without responsible adults.

Fantasy and autonomy

Books set entirely in the familiar world of today reflect the rules of the familiar world, in which most young people have very little choice in their lives, and no real power. There is no story in a reality in which a child makes few decisions beyond ‘vegemite or peanut butter?’ and has no responsibility for themself, let alone anyone else. Most of the children who read my books live timetabled lives, and their freedom to explore and test themselves is limited. In the real world, caring parents want to know where their children are all the time – which largely means confinement to home and garden when not at school or activities.

But children still want to read about their peers practising the autonomy they don’t yet have: deciding what and when to eat, what to do next, how to get out of this mess, which way to go – the reassurance that, with no adults around, you’ll find you’re more capable than you think. There’ll be nail-biting moments, but you’ll look after one another and you would come safely through.

When you experience your real life as dull and predictable, a book is a portal to adventure, to excitement, to dreams, experimentation and possibility. And as a writer, in order to give my characters the autonomy they need to take risks, I will make up a world for them, and throw in a smidgeon of fantasy.

Eirlys Hunter has published two books with Gecko Press, The Mapmakers’ Race and The Uprising: The Mapmakers in Cruxcia.

This piece is adapted from Eirlys Hunter’s talk for the Dorothy Neal White lecture series at the National Library October 2019.

Image credits

First image © Kirsten Slade

Second image © Emma Allen

Third image © Garth Williams

Fourth image © Ole Könnecke from Dulcinea in the Forbidden Forest