By David Colmer, translator

We asked translator David Colmer to write about some of the careful, often hidden decisions he considered while translating the recently released picture story book The Moon Is a Ball.

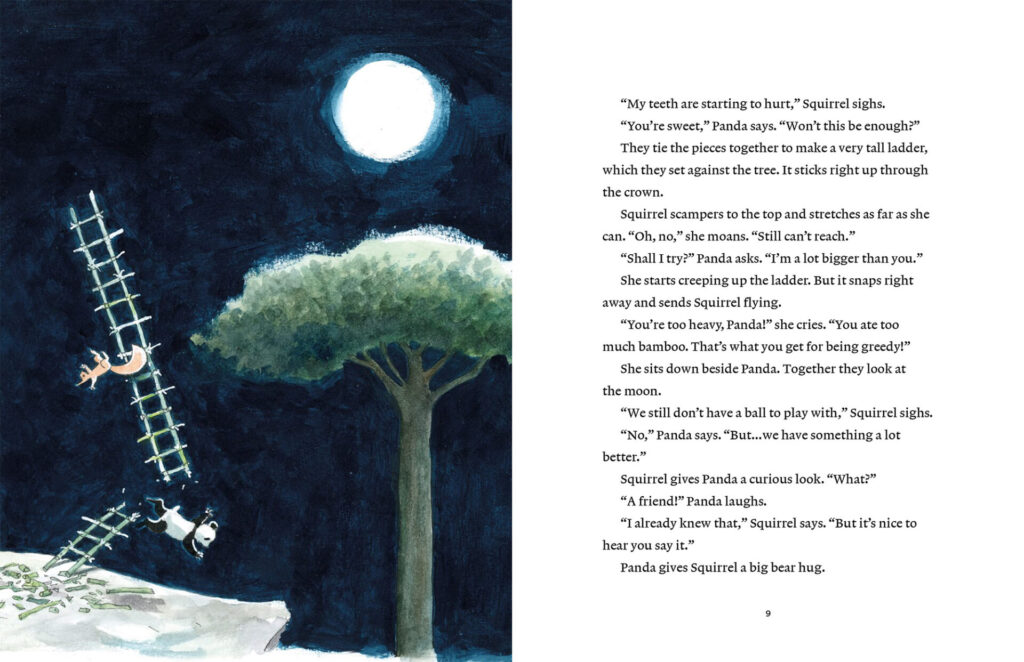

In 2020 Flemish author Ed Franck collaborated with the iconic Dutch illustrator Thé Tjong-Khing to produce their Stories of Panda and Squirrel, charming tales of friendship in which an anthropomorphised panda and squirrel dream, scheme, quarrel and cuddle with all the passion, wide-eyed enthusiasm and naive cleverness of human preschoolers.

My primary task as a translator was to reproduce the flow and fun of the stories, making the English versions as entertaining and easy to read as the originals. At the same time I had to make sure that the characters’ sometimes complicated plans and curious logic didn’t become jumbled or confusing to the children who will be listening to the stories or picking out the words in their first attempts at reading.

Of course I didn’t try to do this by simplifying Panda and Squirrel’s plans, but by taking slight liberties in the literal content to maintain clarity. As a translator I feel that it’s important to always be alert to the most natural or enjoyable way of saying something in English. This allows us to take advantage of the riches the language has to offer, while respecting and conveying the content of the original story.

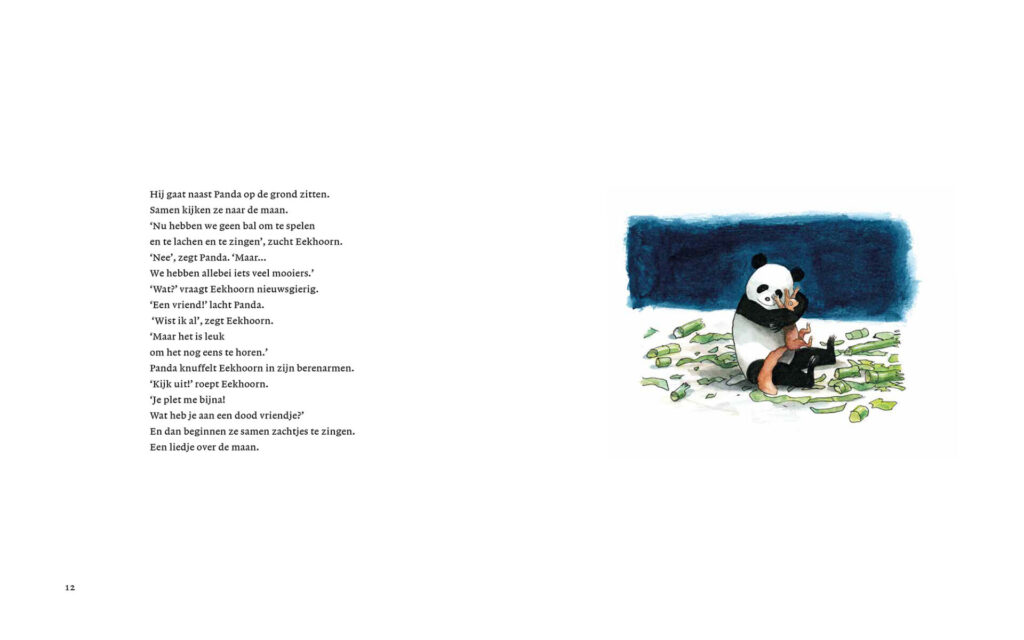

A small example of this process is a short passage from the end of the first story. In the original Dutch this goes:

Panda knuffelt Eekhoorn in zijn berenarmen.

“Kijk uit!” roept Eekhoorn.

“Je plet mij bijna!

Wat heb je aan een dood vriendje?”

Literally translated this would read:

Panda cuddles Squirrel in his bear arms.

“Careful!” cries Squirrel.

“You’re almost crushing me!

What good will a dead friend be to you?”

In my published translation it has become:

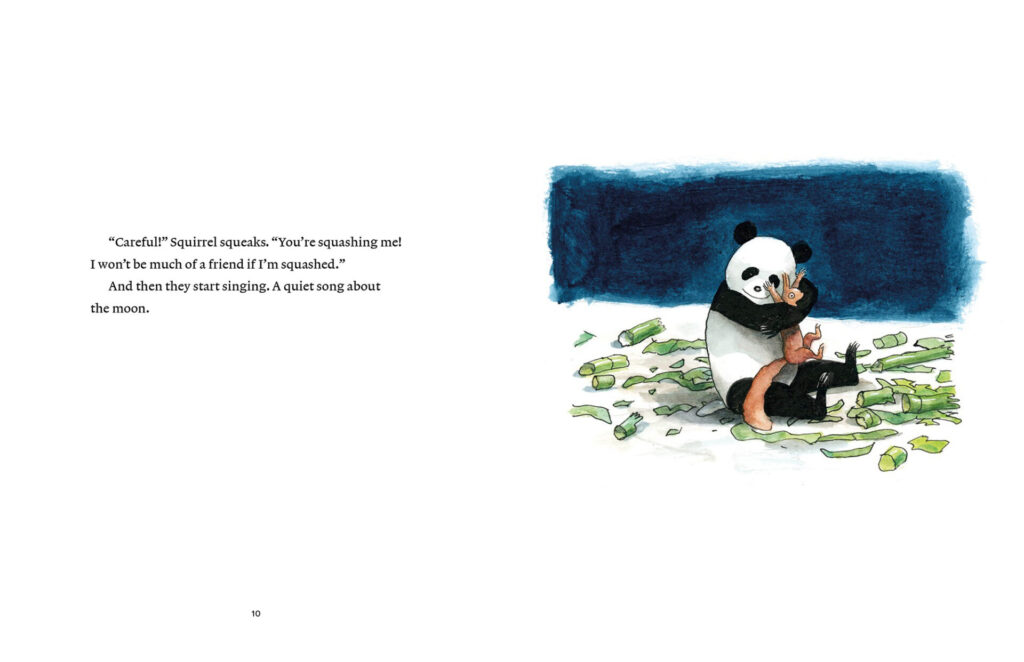

Panda gives Squirrel a big bear hug.

“Careful!” Squirrel squeaks. “You’re squashing me! I won’t be much of a friend if I’m squashed.”

Dutch has a wonderful ability to combine two words to make a new one and “berenarmen” in the first line is a typical example. It means a bear’s arms and it is perfectly clear to any Dutch reader. In English you could say “bear arms” or “bear’s arms” or even “ursine arms”, if you wanted to see the kids scratch their heads. The first two options are reasonable but suffer from interference from English homonyms. A listener could hear “bear arms” as “bare arms” and think, what’s happened to Panda’s fur? “Bear’s arms” sounds like the martial “bears arms”. At the same time English has the expression “bear hug”, which is so lovely it would be churlish not to use it here.

In the next lines I’ve rendered “roept” (literally “cries”, “calls” or “shouts”) as “squeaks”. This is partly because Dutch bears a lot of repetition of this word, whereas English tends to reserve it for occasions where there is a clear distinction from something like “say”, and partly to once again accept the gifts the language offers. Besides fitting the situation best, “squeaks” alliterates beautifully and adds an expressive and comical note.

Lastly I’ve changed the last two sentences because Franck is using the verb “pletten”, meaning to crush or squash, in an absolute sense that allows him to qualify it with “almost”, while in the English “squash” is more a process that can lead to becoming “squashed”, and it is much more natural to make that explicit by using both terms. I didn’t include the word “dead” in this passage because it is implicit in the state of being squashed, and would sound much crasser in English than it does in Dutch.

As you may have noticed, there are some fundamental differences between the Dutch and the published English. First, the layout. The Dutch is published almost as a long poem with a new line for each clause. This is quite common in Dutch children’s books, but would be an unnecessary contortion in English, as it requires you to translate each clause to more or less the same length only to produce an unfamiliar format. Better here to stick to normal paragraphs, as it makes it easier to keep the flow of the stories.

As you may have noticed, there are some fundamental differences between the Dutch and the published English. First, the layout. The Dutch is published almost as a long poem with a new line for each clause. This is quite common in Dutch children’s books, but would be an unnecessary contortion in English, as it requires you to translate each clause to more or less the same length only to produce an unfamiliar format. Better here to stick to normal paragraphs, as it makes it easier to keep the flow of the stories.

Second and crucially, Panda is a “he” in Dutch but a “she” in my English version. This brings us to the thorny issue of gender. Like French and German, Dutch is a language that has grammatical gender, and in Dutch almost all animals are “he”. This doesn’t necessarily coincide with the physical gender of the animal in question and when first learning Dutch I was often confused by the way Dutch people could refer to dogs or cats that were known to be female as “he”. In Franck’s Panda and Squirrel stories, all the animal characters are “he” and this usage corresponds most closely to English “it”.

In English, though, “it” is inconsistent with personification. As soon as a character becomes a person, gender is assigned. I did consider “they” as an ungendered singular pronoun, but didn’t use it because although it has a long history as a singular noun of general personal reference (“If someone calls, tell them I’ll be back at six.“), it is still quite marked when used for specific individuals (“My friend Madison raised their hand.”).

In these stories I didn’t want to make all the characters male and I didn’t want to assign gender according to behavioural stereotypes. I was also leery of making the main characters of these stories of friendship male and female, as they could then be interpreted as a heterosexual couple. My solution was to make both Panda and Squirrel female and provide a mix of genders for the minor characters (some, like the peacock, are drawn as male). After I explained the problem to Ed Franck, he was more than happy to go along with this tactic.

It’s always strange when a translation has gone out into the world, as you often have no idea if it’s being read and enjoyed at all. In this case though I was delighted to get a message on WhatsApp that my four-year-old granddaughter couldn’t get enough of Panda and Squirrel but wanted to hear the stories over and over again and kept laughing each time: “Grampa’s made a funny book!”

David Colmer is an Australian writer and translator who lives in Amsterdam. He has won many prizes for his translations of Dutch literature.

The Moon Is a Ball is available now from all good bookstores and our website.