BY ELAINE REESE

Young children naturally gravitate to the illustrations in picture books. Eye-gaze studies, in which cameras carefully track children’s attention, show young children look at the pictures over 90% of the time during picture-book reading, and only rarely at the words.

Adults are another story. We look at the pictures too, of course, but our eyes are drawn to the text because we need to read the story’s words for our children.

Wordless picture books can be magical. With no text pulling our eyes away, adults and children can explore the pictures together, and together tell the story.

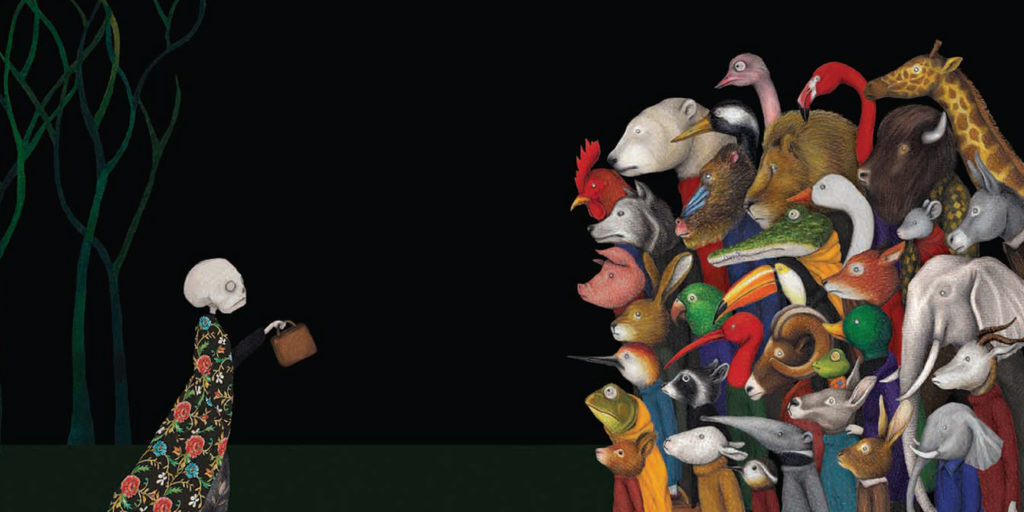

Gecko Press’s new release Migrants by Issa Watanabe is a compelling example. The saturated illustrations of animals migrating to their new land rivet the viewer. Without print tying us down, stories are creative, akin to improvisational jazz. Your story will be different with each telling.

From Migrants

Wordless picture book stories can also generate more collaboration between adult and child. In one study, teachers shared a wordless picture book called The Treasure Thief by Beatrice Rodríguez — a sequel to Gecko Press’ bestseller The Chicken Thief — with small groups of preschool children. Compared to the reading of a traditional texted picture book, children talked more and used more diverse vocabulary during the wordless picture book.

From The Chicken Thief

In the study, teachers spent more time with the wordless picture book than the texted book, and engaged in higher quality conversations during the wordless picture book in which they helped children learn new concepts. Whenever children talk more about a book, and adults teach new concepts from the book, children’s language and literacy skills grow.

Best of all, wordless picture book stories can be told in any language. Tell the tale together in te reo Māori if you and your child are able, or in any language you and your child both know.

The only downside? Making up your own story can feel daunting. Sharing a wordless picture book together can require more creative energy on your part, and for your child. Although you can explore these books at bedtime by simply gazing together at the pictures and commenting on occasion, it’s probably better to pick a time in the day when you’re both well-rested and brimming with energy to fashion a story together — perhaps after a sleep for your child and a coffee for you!

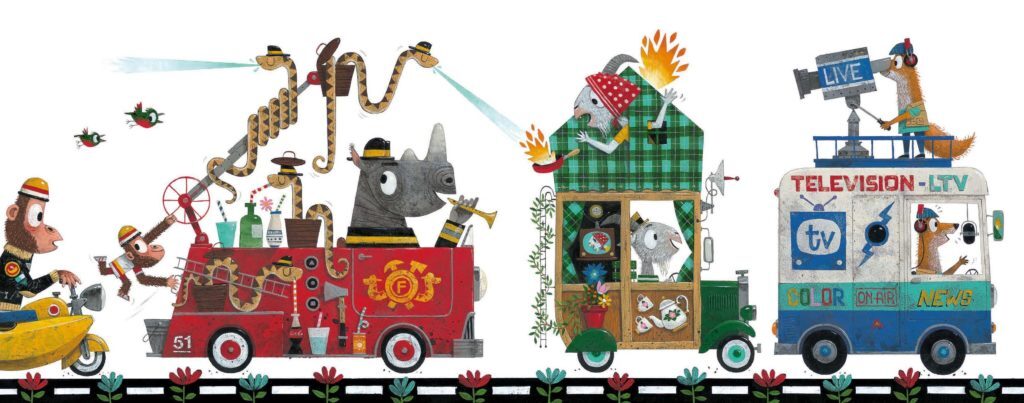

From BANG

The beauty of wordless picture books is that you will take more joy in discovering the pictures along with your child. You’ll be more attuned to their gaze and can follow in on the parts of the pictures they want to talk about. Higher levels of joint attention help your child learn new words from books.

The story options are endless, but here are a few styles you can tailor to different books and to your child. Each has pros and cons:

The storytelling style:

Some lucky parents love to spin tales at the drop of a hat. With this style, you can have fun telling as wild a tale as you wish, complete with character voices and dramatic pauses and volume shifts. This performer style is captivating for all ages, and can be a highly effective way for older children to learn new words, especially if you define new words in conversation after the story. Migrants is the perfect book for this style because parents may want to take the lead when introducing weighty themes such as death.

From Migrants

Just make sure you don’t get so carried away with your story that you are no longer paying attention to your child. Some parents may also feel put on the spot by the storytelling style.

The collaborative style:

You and your child create the story together. This style is my personal favourite, and it’s backed up by scores of studies demonstrating benefits for children’s language development and their understanding of stories and emotions. Start by simply having a conversation about what’s going on in each page. Leo Timmers’ Monkey on the Run is a delight for collaborative storytelling; the rich pictures ensure you and your child will find a new detail to discuss each time. With re-reading and with older children, you can co-create a storyline extending throughout the book.

From Monkey on the Run

Here’s a charming example of two children together telling the story of The Chicken Thief. Most children enjoy this style, but watch that you don’t end up with two parallel storylines instead of an interactive whole that builds upon each other’s contributions.

The story assistant style:

With older, highly verbal, or energetic children, you may want to take a back seat to let them tell the story. Offer your help at key junctures only if they get stuck. This style could even work with infants and toddlers who love to babble and chatter when looking at a high-contrast book like Janik Coat’s gorgeous Aleph, as long as you accept whatever bits and pieces of story come your way.

From Aleph

The drawback of the story assistant style is that some parents find it difficult to listen raptly and respond, but not take over. Active listening is well worth the effort; children of all ages love and need to feel truly heard by adults.

So be brave, have fun, and let the pictures take centre stage.

Here are some other wonderful wordless picture books to try:

The Snowman by Raymond Briggs

Mirror by Jeannie Baker

Chalk by Bill Thomson

A Ball for Daisy by Chris Raschka

Journey by Aaron Becker

Elaine Reese is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Otago, who received her M.A. and Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. Elaine conducts research on how children learn from picture books and everyday conversations. She is an advisor for the Growing Up in New Zealand longitudinal study and wrote Tell Me a Story: Sharing Stories to Enrich Your Child’s World, published by Oxford University Press.

Want to hear more from Gecko Press? Every month we send out a newsletter with all of our latest blog articles, activity sheets, and sometimes a competition too! Sign up to our mailing list here.