Issa Watanabe was born in Peru in 1980, the daughter of an illustrator and a poet.

She studied Literature and Fine Arts and Illustration and is the author and illustrator of a number of books.

Migrants is a vital and powerful wordless picture book of courage, loss and hope—the definitive story of what it takes to migrate to a new land.

Why did you want to tell the story in Migrants?

In the year 2000, I went to live in Mallorca. Soon after arriving, it became common to see images in the news of migrants landing on the island’s shores after arduous journeys across the Mediterranean. For the most part the media images showed people being turned into numbers, or morphing into a faceless human mass.

One day, I met Abdulai, who had arrived in Palma after a very long journey from Bamako in Mali. He ended up living with us and, during that year, not only did we hear of the harsh conditions that led Abdulai to say goodbye to his family and start the journey, but also what it meant for him to try to settle in a country that didn’t want him.

Many years later, I saw Magnus Wennman’s photographs of Syrian children, “Where the Children Sleep”. The looks on those children’s faces, some in an improvised camp in a forest, moved me deeply, and I did the only thing I could do: draw. This first drawing was followed by another one and, little by little, I started telling a story without planning to.

What would you like your audience to read in this story?

I think this book is about empathy. Being moved by a character in the story helps us empathise with the human beings who are going through such a challenging experience. It has always surprised me how empathy can start a conversation with children and adolescents, and generate further reflection.

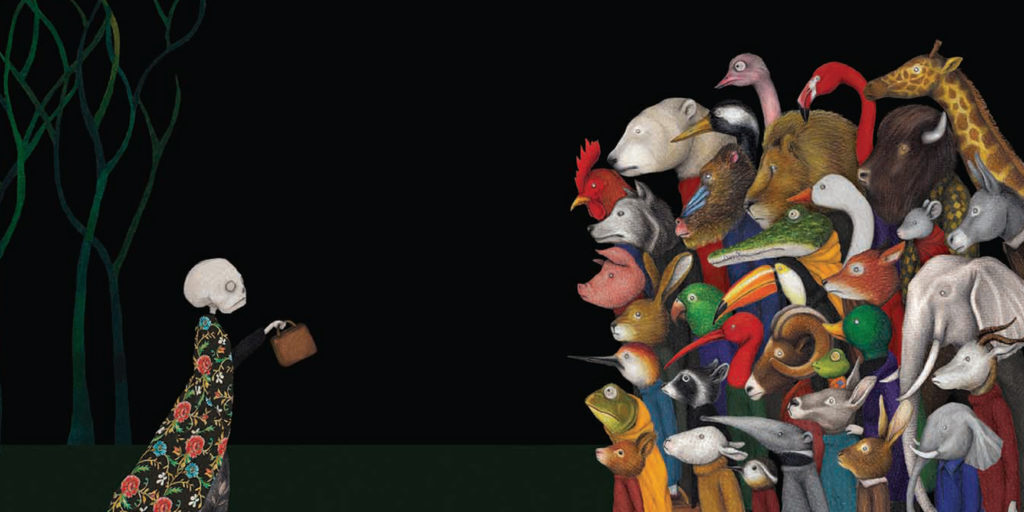

Sometimes, we overprotect our children and we try to avoid sad stories and difficult themes. This tale is graphic: it is a sad story because forced migration is a sad theme, and it is important that it is told this way. The book tells the journey of a group of ‘animals’ who are forced to leave their homes. It is the story of the path they have to take, the hurt and sacrifice that it entails, but also the underlying hope.

This hope is represented by the strong bond between the members of the group who show kindness and mutual help; by the use of colour against a dark background; by the strength which pushes them to keep going despite the hardship; and by the end of the journey. The end is about hope, but it is also about the responsibility of those who welcome the migrants.

Why did you choose to tell this story without words?

When I think of a story, I always have a mental picture of a series of images. I express my emotions or tell a story through images. However, in this particular case, when you get closer to this theme—by doing some research, by watching the news and seeing real images of what is actually happening—it moves you. My father, who was a poet, once wrote, “When faced with horror, all I can do is allow myself this silent poem.” When you look at Migrants, you encounter this silence.

Why did you choose animal characters?

Animals allow me to tell the story in a way that human representations couldn’t. If I had chosen to do the latter, children would have struggled to relate in the same way they would when such a hard and sad story is illustrated with images of fantasy. Children empathise quickly with animals. Also, animals allow the story to be told without mentioning cultures, race, a particular ethnic group, so the story becomes universal.

Have you been surprised by the readers’ own interpretations?

Very much so. I was invited to talk at schools that had been “working on the book for several days” and, in some cases, they had written their own text. Some of the interpretations and texts were wonderful. All of it: from the questions they asked when I presented the book; how it was interpreted by very young children and adults alike; and how each person felt or was moved by it.

Can you talk about your use of colour and light in the illustrations?

I wanted to show the contrast between life and the sadness and difficulty of the journey. Colour expresses hope. Darkness is more like silence. But more than anything, I wanted each character to have their own identity defined by each detail: the care I gave to clothes, the choice of colours, and the characters’ expressions. The first thing that happens with migrants is that they are turned into numbers, or morph into a faceless human mass, which we cannot identify with.

What are the key symbols of the book?

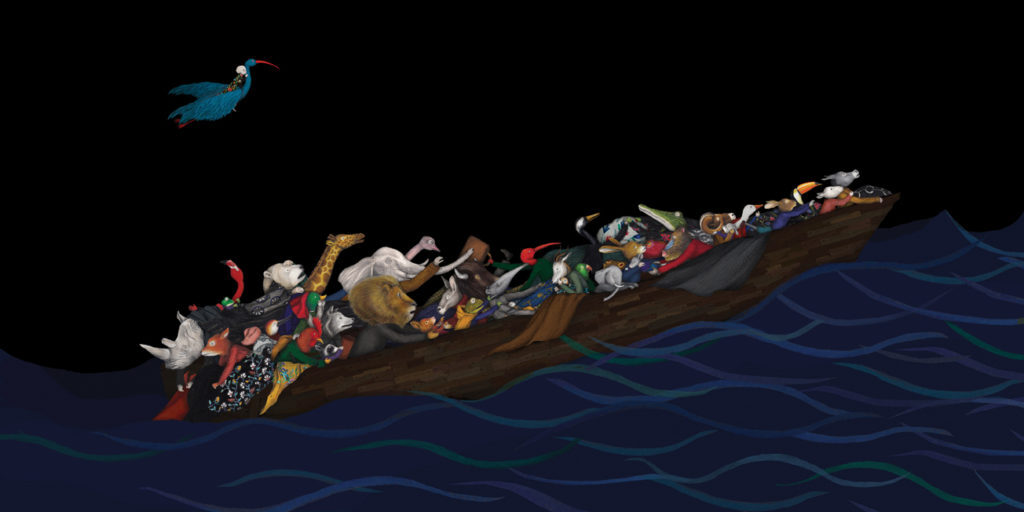

The bird is a blue ibis, which in many cultures represents the one who communicates between life and death, the past and the present.

The forest was present from my first drawing. It came up from seeing those photos of children asleep in a forest. But, as the migrants go through more hardship, the forest also represents a “desert” that never seems to end.

What is happening when death meets the polar bear?

This illustration was created while the book was being edited, and readers have expressed many opinions about it. The bear appears for the first time in the book in its ‘animal’ state (naked, wild, instinctive). It is facing death, against a floral background, similar to the one in the last drawing. This illustration is placed between the image of the animals sleeping (in the forest) and the image of the animals awake, waiting to get on the boat. Some interpret it as a dream.

What is your migration story?

My paternal grandfather immigrated by boat to the north of Peru from Japan. My maternal grandfather came from Switzerland and met my grandmother. She was the daughter of a Spanish immigrant who’d settled in the north of Peru. I was born in Peru, and when I was 20, I went to live in Mallorca where my daughter was born. After 15 years there, I moved back to Peru.

What is your process? How do you create and work with your illustrations?

I am disorganised. I have several drawings that I keep working on intuitively until I get a clear structure. I like working on my own. I dislike working with a computer: I like the experience the physical material provides. I like artisanal work. I don’t often work digitally with my illustrations. Maybe this means that I spend more time and get more involved with each project.

Migrants is available now from wherever you buy or consume your books and on our website.

Migrants is available now from wherever you buy or consume your books and on our website.

Want to hear more from Gecko Press? Every month we send out a newsletter with all of our latest blog articles, activity sheets, and sometimes a competition too! Sign up to our mailing list here.