Blexbolex creates books that compel us to keep coming back, and images—and thoughts—that remain with us long after the book is closed.

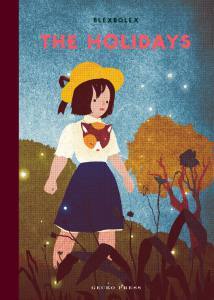

The Holidays, has been awarded Pépite 2017—the French most prestigious children’s book award—at the Montreuil Children’s Book Fair.

Blexbolex answered our questions about The Holidays:

How would you describe what the book is about?

Here is a simple synopsis: at the end of the summer, a girl spends time at her grandfather’s place in the countryside. Then an unexpected guest arrives, who the girl doesn’t like.

Through images and the characters’ actions, the book tells the story of those few days and what happens. More generally, the story is about missed opportunities. It’s about the assumptions we make that aren’t always right.

The girl likes to control and enjoy her space and her time, and decides these can’t be shared. She isn’t mean, she just doesn’t understand that this time and space exist for others as well. She chooses to ignore it. She makes a mistake and will eventually regret it – the mistake is revealed, true faces are shown.

So, it’s the story of an experience.

How do you write a book without words? Do you only think in pictures? What is your story-writing process?

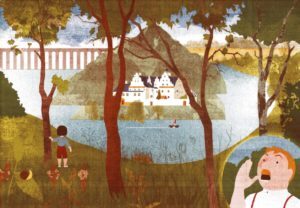

First, you must build a plan. Here it’s the characters and the scenery. The secluded location of the house makes this little drama possible. We are in an imaginary area, similar to a fairytale or to what could be a puppet show. This is the frame for the action, which plays out like a fable. The entire story takes place within an area of around three square kilometres. This is very small, but it offers many possibilities.

Then I think about characters’ roles and functions, about the topography of the place, to build a credible setting, and then the timeframes in which actions occur.

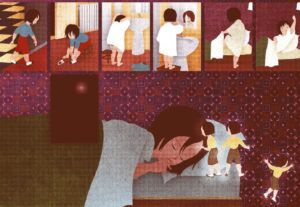

I see this book as a sort of theatre. Usually the double-page image is a scene and the vignettes – generally at the rim of the pages – are actions that take place within it. The book is – very classically – divided in four acts and (almost) each double page is a scene. It’s a play that takes place in a book rather than on a stage.

I see this book as a sort of theatre. Usually the double-page image is a scene and the vignettes – generally at the rim of the pages – are actions that take place within it. The book is – very classically – divided in four acts and (almost) each double page is a scene. It’s a play that takes place in a book rather than on a stage.

In the book, I use styles of narration from the cinema and from comics. I choose these to fit with what I want to say.

I had to build a grammar – both visual and narrative – that was clear enough for the pictures to entice a reading.

What do you say to someone who says you can’t read without words?

I would probably ask them to define “reading”!

A text doesn’t mean anything without context. What’s the link between me, a lettuce and the word “eat”? What’s the link between past, present and future? What’s the link between doubt, certainty and probability? Without those links – which are organic – all of the world’s vocabulary is useless. We must build nets of connection to make sense. These connections can be through common sense or dramatic construction.

As a linear system, text seems the ideal medium to make sense, but reading depends on our ability to link things together through memory, thinking or imagination.

It’s not so different with images. It’s a different language, but it is still a language. Would you turn down the chance to go to the opera or to a concert, a play or a movie, to look at a painting or to read a poem, on the pretext that there is nothing to understand or to feel? I don’t think so. Text itself doesn’t guarantee you will understand or feel something. Reading is performative and demands effort from the reader.

What is your work process?

I have no idea! I’d love to know…

How do you come up with new story ideas? What is your inspiration?

I read, listen to music, go to shows when I can, and I like when people tell me their experiences – you have to take time to understand them, and it can be enriching. When I have time to take a walk, I try to mentally record every detail – the daylight colour, the clouds’ shapes, the plants, the attitude or clothing of a passerby. I don’t take notes or sketches; I try to retain what hit me. That’s a way to keep up my visual memory and my imagination.

Ideas find me. I never find them. These miscellanies of memory and impression make me think that yes, there is something to do here. So I don’t have any methodology. This comes only when I’m about to start creating the idea and plan out my work.

Adults love your work as much as children… Who do you have in mind when you work?

Nobody. I have too much to do thinking about what I’m doing. Occasionally a book or part of a book, or even just an image or a fragment of this image is intended for somebody in particular. But even then I want to make it accessible to others as well.

Is the response the same from adults as from children?

I can’t really tell. I publish my books – which means that everybody has the opportunity to read them or not, to like them or not. Sometimes, my books seem difficult to some adults, but not at all to children.

The adult audience seems to enjoy the graphical finish or the colours and the production effort. This aspect may be less interesting to children, who seem to be interested in images and their contents more than their form. Note that I say “seem”, because some children will be more aware of the materials, the format and the sensory experience.

A book has to live its own life and try to enter the minds of those who read it. Sometimes it can fail, other times it can work very well. I don’t know the recipe. My books are for everybody, which doesn’t mean that everybody can or must like them.

Why did you choose this format for The Holiday and can you describe some of the detail of production and printing, how you got the colours exactly right, etc?

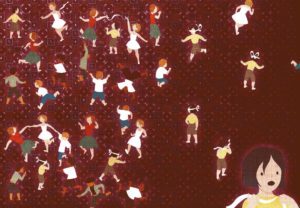

I chose this format because I wanted something small and robust. The book has 128 pages, so there is a relationship between its height, width and thickness. I chose the page size to suit the characters and the figures – how they had to be depicted to hold the action. And finally because large surfaces would have forced me to enrich them too artificially – and that would have threatened the readability. For instance, when the girl takes up the whole page, the emotional relationship between the character and the reader is kept: she is still a character, similar to a doll or puppet. A few extra centimetres could be enough to break this relationship.

Sometimes, working on a computer makes scale, space and positioning objects in the space complicated. If I want to have an overview, I need to reduce the window, so I don’t see the detail. The small format gives me better control of those issues.

The control of colours has been a real challenge with this book. When we were testing the printing, we discovered that what I saw on my screen had no reality when printed. The colour is complex, which required us to anticipate what could happen during the production. We changed the process right at the end to a simplified system that I had tested with a previous book.

The choice of materials is important. They define an atmosphere, almost more tacitly than visually. Through the sense of touch, we pass on information that would be long and complicated – even impossible – to pass on by other means. A book can talk to your senses as well as your intellect.

What are you working on now? Can we have a sneak preview?

Hahaha! No. This will be kept secret. I don’t make only children’s books. And I don’t make only books. But I know that those activities will generate new ideas sooner or later. We just have to wait – which I also do. I wait for the next book that will come to me. And I’ll be delighted when it is there, in front of me – asking to exist.

Books by Blexbolex

The Holidays will be released in March 2018 (preorder now at geckopress.com).