Catharina Valckx was born in 1957 in the Netherlands. She grew up in France and now lives in Amsterdam. She has written and illustrated over thirty books and been nominated four times for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award. Her books are published in more than eleven languages and have won numerous awards.

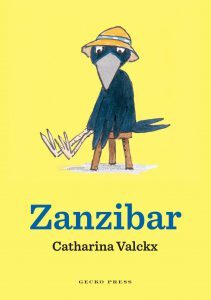

Zanzibar, an uplifting, warmhearted book about a crow who proves you can perform truly heroic deeds if you believe in yourself, will be released in August.

How did you become a writer?

By reading. In my early twenties, I noticed that I loved particular books very much, not because of their topics but for their writing. Authors like André Gide, Giono, Beckett, Simenon. I grew up in France, and after I finished high school, I went to an art school in the Netherlands. My parents are Dutch, and I wanted to know my roots, and to travel. I was happy in the Netherlands, but I missed the French language. So I started writing in French, for fun, made- up stories. I also wrote lots of letters. I think that’s how I found my style and the tone of my writing. Much later, when I wanted to write a picture book for children, it felt obvious to me, with my training in visual art, that I would also draw the illustrations. Soon I began writing books with more text—reading books.

Your characters often have a dry and slightly sideways approach to the world—do you think you are attracted to particular kinds of characters?

It’s not something I decide logically, or even consciously. I think I like characters that aren’t perfect. A particular kind of character turns up often. They are like a child: naive, enthusiastic, altruistic, tolerant: fundamentally nice. They are open to friendship and to warm contact. The sideways aspect is in the situations, what happens in the story, the dialogue. It often comes from using a kind of reasoning that looks logical but isn’t. I look for the absurd more than anything else. It’s a way to look at reality from a little distance—it’s refreshing. But it’s also the hardest. You have to think out of the box.

Are there themes you like to write about in your books for younger readers?

Friendship, which goes with tolerance and acceptance of difference. Sometimes, loneliness turns up—in French we have a saying: loneliness ‘shows its sad nose.’ Characters have very frank relationships. In my books, there is no pettiness. There is a nice atmosphere. I describe the world as I would like it to be, as a possibility. There are, of course, bad guys, but I always defuse them quickly. I want to write comforting books, probably because I remember that the world can be scary when you’re a child.

The other theme that matters to me is the love of nature in its diversity and beauty, in all seasons. I’m not referring to environmental issues. I think children must learn to love and to know the earth first—its flora and fauna, its landscapes—before being confronted with our terrible current state of degradation, destruction and emergency. Children have the right to be carefree before getting responsibilities; they have the right to dream before freaking out.

How important is humour for you in children’s books?

In children’s books in general, I don’t know. It’s possible, of course, to write a very good book that isn’t funny. Books that are poetic or educational or just beautiful. But for me personally, humour is essential. It’s the oxygen that feeds the fire. I particularly love absurd humour. I often notice that children are receptive to it, even very young. What touches me the most is when a book is funny and poetic. Like Arnold Lobel’s stories Frog and Toad or Owl at Home. These stories have something sad at their heart, which makes them feel complete and moving. Humour is a way to handle reality more easily, because to laugh, you need a little distance. It’s a way to put things into perspective, to not take life too seriously.

Sometimes you illustrate your own books and sometimes you work with other illustrators—how does this process work?

I’ve always illustrated my own books, until 2015 when I wanted to work with Nicolas Hubesch —a French illustrator who lives in Athens and whom I admire very much. It was simply for the pleasure of working together. Nicolas has a specific humour and good-heartedness in his drawings, which really speaks to me. [Nicolas Hubesch illustrated Catharina Valckx’s Bruno, published by Gecko Press in 2017] It’s very enriching to work with an illustrator, especially when he is as good as Nicolas. (Although I also love doing everything myself and being the only captain on board.)

How did you create the illustrations for this book—what medium/tools and process?

I made this book at a time when my publisher needed black-and-white or two-colour illustrations. (It was a question of cost but since then colour printing has become cheaper.) I hand-drew with India ink and an orange pencil. Now, I often go over my drawings on the computer— sometimes I even make them entirely on computer— but the drawings in Zanzibar are traditional, with no retouching.

Can you recommend some books for early readers that were originally written in French?

My favourite books written in French for young readers aren’t translated into English. For instance, Nono Ouvre un Magasin or La Baguette qui Marchait Pas by Nadja, or the stories of Grignotin et Mentalo by Delphine Bournay. I can warmly recommend Poor Little Witch Girl by Marie Desplechin, and of course the comics Asterix and Obélix (Goscinny et Uderzo), Tintin (Hergé), Gaston Lagaffe (Franquin) … all are classics that I loved.