Jonathan King is a filmmaker and comic creator. His comics have featured online and in anthologies. And his debut feature Black Sheep remains one of New Zealand’s biggest-selling feature films.

Jonathan King is a filmmaker and comic creator. His comics have featured online and in anthologies. And his debut feature Black Sheep remains one of New Zealand’s biggest-selling feature films.

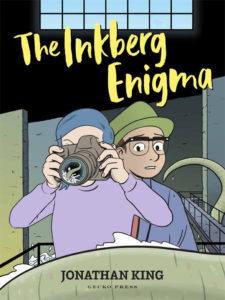

The Inkberg Enigma is his first graphic novel for children.

It’s a mystery adventure in which an unlikely pair uncover the secret that has corrupted a town.

Why is this a comic and not a film?

This was only ever going to be a comic (which is not to say it couldn’t one day be a film) and I approached to quite differently from any film I’ve made or hoped to make.

I had the world of the story, the look of the characters, the feel of the story before I’d pinned down quite what the story was. I started drawing before I really knew everything that would happen – which would be a bit like shooting before you’ve finished the script!

What did you enjoy about the process of drawing a comic in contrast to a film?

What I love about drawing a comic is that the challenges (and it is challenging) are all your own. That is to say, you’re not worried about budget, you’re not worried about the weather, you’re not worrying about actors’ performances. With drawing a comic, sometimes you’re limited by your ability, your patience, your research, but when you achieve or surpass what you hoped for, the feeling is incredible.

In fact, what is the process for making a graphic novel? What tools do you use?

It’s a very slow process — certainly with my style. You can’t rush it — at least not without it being obvious. You’ve. Got. To. Draw. Each. Thing. In. The. Book. I will thumbnail how the whole page will fit together but then you have to take it panel by panel. It’s not til the whole page is done that you can step back and see what you’ve got.

I think a lot about how pages will face each other, and what each page turn gives you: surprises are good on a left hand page, so the reader doesn’t see them coming; suspense is good to end at the bottom of a right hand page, to keep the reader turning the page for more.

I often use reference — for some particular buildings, boats and vehicles. Some things in the book I made 3D models of, so I could position them how I wanted. But even then, it was all drawn by hand — albeit with an electronic pencil into a digital tablet — mostly an iPad.

I use software called Clip Studio, which has tools (like speech bubbles, panel borders) designed for comics, and sets of different ‘brushes’ — all designed to emulate old fashioned analogue media. I love working digitally — for the flexibility and the cheats I can do behind the scenes but want it to look organic and hand made.

How long did it take you to write and draw The Inkberg Enigma?

It took about three years — made longer by some digressions early on, when I started drawing before I’d written enough.

There’s a definite sense of place in the book – are they imaginary or did you have particular places in mind?

The world in the book is largely based on a real harbour in the South Island of New Zealand, called Lyttelton Harbour — where the town of Lyttelton faces the smaller settlement of Diamond Harbour, connected, as in the book, by a ferry. The town of Aurora is mostly based on Lyttelton, with a dash of a city in Oregon, USA, called Astoria and Cannery Row in Monterey, California. The castle in the book is based on Larnach Castle in Dunedin, New Zealand.

Your book is full of references to other books – are these particular books that influenced you or are important to this book in some way?

The biggest influence on the book is probably the Tintin books by Hergé. Although my protagonists are very different from the legendary boy reporter. I loved the adventures he got into — usual mixing thrilling plots and disreputable baddies with a dash of the fantastic.

Some other books name checked in the book are absolutely influences on the kind of mystery and adventure I wanted to evoke, and were hugely important to me as a young reader.

Certainly Miro’s compulsive book collecting is something I’m guilty of myself, and I have some two thousand books at home.

Who are your comic book influences?

My first comic influence was Hergé, whose careful ligne claire (clear line) style I’ve loved since I got my first Tintin book (The Black Island) when I was four.

Since then I’ve been influenced by a French cartoonist, himself influenced by Hergé called Yves Chaland and an American cartoonist called Darwyn Cooke — who has a very different, but very graphic and almost old-fashioned style. Sadly all three of those amazing artists are no longer with us.

Another big influence on my work was New Zealand cartoonist Dylan Horrocks, who loves Tintin as much as I do, and has been hugely encouraging to me (and many others) about making comics.

Which cartoonists and storytellers today do you particularly admire?

Some of my favourite comics makers working today are Aaron Renier, whose book The Unsinkable Walker Bean is a terrific adventure. I love the work of New Zealand illustrators and cartoonists Sharon Murdoch and Giselle Clarkson and, as I said above, Dylan Horrocks.

I adore the Mortal Engines series of books by Philip Reeve. I loved The Murderer’s Ape, by Jakob Wegelius.

My favourite filmmakers working today include Guillermo del Toro (who is every bit as nice a person as he is good a filmmaker), Wes Anderson and Michel Gondry.

The Inkberg Enigma is available now from wherever you buy or consume your books and on our website.

Want to hear more from Gecko Press? Every month we send out a newsletter with all of our latest blog articles, activity sheets, and sometimes a competition too! Sign up to our mailing list here.