Ulrich Hub trained as an actor and now lives in Berlin, Germany. He works as a director for stage and writes plays, screenplays and children’s books, which have won numerous awards. His previous books include Meet at the Ark at Eight and Duck’s Backyard.

His new book, One Wise Sheep, is a comic retelling of the nativity story from the point of view of the sheep, in which the flock go looking for their lost shepherds—and the rumoured newborn child—in an adventure-filled nighttime hike across country.

First the Noah’s Ark story in Meet at the Ark at Eight and now you have a new interpretation of the Christmas story—is nothing sacred to you?

I’m suspicious of anything that’s supposed to be sacred. On my bookshelf, the Bible sits alongside Grimm’s Fairytales, the Greek myths and One Thousand and One Nights. These books are all packed with fantastic stories and characters based on a crucial question: what do we believe in? Whom do we believe? And why? The answer, obviously, doesn’t have to be a God or a church.

What do you believe in?

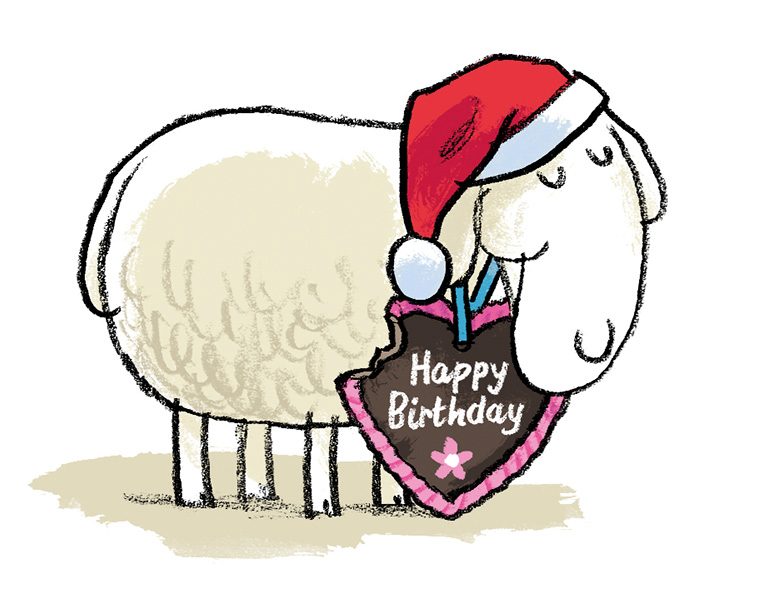

To be honest, I was never entirely convinced that Jesus was a member of God’s family and could turn his cross into a flowerpot with a single word. But nobody could possibly object to his message: “Be a bit kinder to one another, forgive your enemies, and welcome everyone—especially children.” Christmas is a bit of a damp squib for me nowadays, but its message is spot on: “Fear not.”

Why did you choose to tell the story through the eyes of the sheep?

I’d always been struck by the fact that sheep—who have a starring role in every Nativity story—don’t appear in the New Testament. The shepherds in the fields are just told, “you’ll find the baby wrapped in swaddling clothes,” and they set straight off. There’s barely a mention of a crib or a stable, and no mention of an ox or an ass. So the baby could just as easily be lying in a shoebox under a motorway bridge.

swaddling clothes,” and they set straight off. There’s barely a mention of a crib or a stable, and no mention of an ox or an ass. So the baby could just as easily be lying in a shoebox under a motorway bridge.

Did you take inspiration from sources other than the Bible?

While writing this book, I read my unfinished manuscript aloud to children at schools in Berlin and chatted with them afterwards. This had a significant influence on the finished story.

I also like Pieter Bruegel’s picture The Census at Bethlehem, which depicts a Flemish village. The artist captures the reaction of his contemporaries to the arrival of Mary and Joseph—they don’t realise what’s going on because they’re all busy with other things: eating, counting their money and having snowball fights. If this story is still supposed to speak to us, it has to be relevant to all eras.

What is One Wise Sheep trying to tell us?

First and foremost, it’s supposed to entertain children. However, it’s also important that the sheep just blithely set off, and then end up missing the actual event—because they keep on waiting for one another and even take the last one under their collective wing. This kind of care for others has become less evident in recent times.

Why do the sheep think that the newborn baby is a girl?

Isn’t it striking that all saviour figures in our culture are male? Even among modern superheroes, there’s barely a single woman. The sheep also wonder why that’s the case. In the playscript of the story, the question as to whether girls are cleverer than boys is discussed in much more detail—something that causes quite a stir with the audience. When a sheep said in a recent production: “Girls are never going to save the world. They’re too—” a child shouted out: “Watch what you’re saying!”

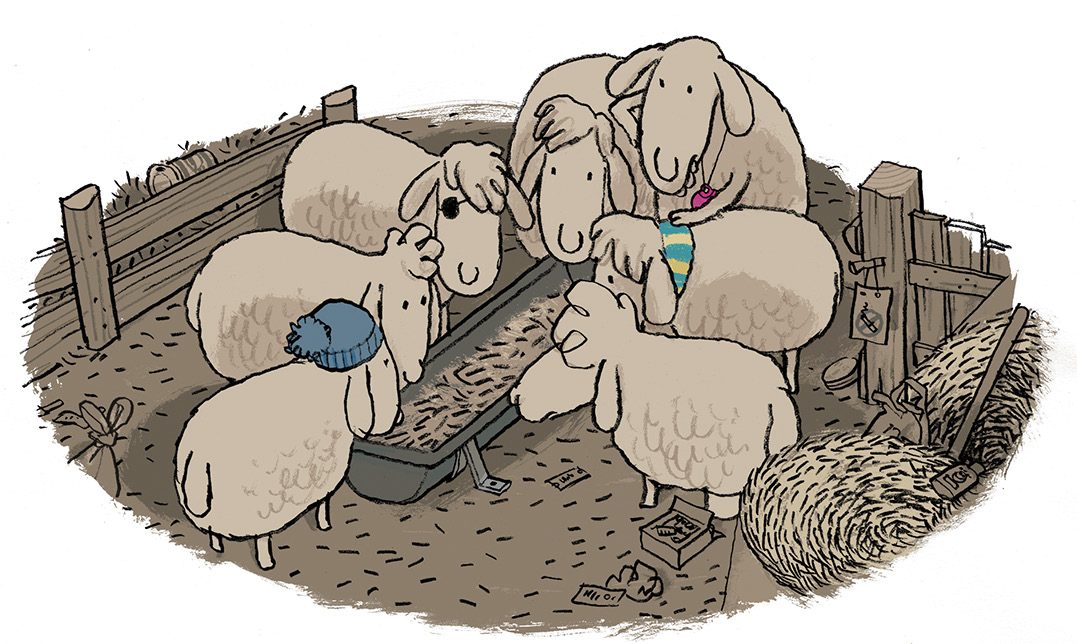

Why don’t the sheep have names?

They do have names—the sheep with the side parting, the one with the bobble hat, the one with the retainer and so on. If I’d given them “proper” names, gendering them would have been unavoidable. So children can decide for themselves which sheep are girls and which are boys. To judge by my experience of reading the story to children, opinions vary wildly—which is fantastic.

How does your collaboration with Jörg Mühle work?

I send him regular first drafts, and he then starts to work on the illustrations. Jörg Mühle’s figures are the perfect mixture of delightful and completely anarchic. When I visited him in Frankfurt, he allowed me to look in his sketch book—there were at least 500 different sheep in it. You could have made a sheep museum of them! He let me choose the sheep I liked best.

You obviously enjoy humour in children’s books…

Humour is essential for me. I don’t write any differently for children or adults. Often laughing is the only way for me to handle a desperate situation. We Germans tend to be too serious, and comedy is not so highly regarded. Often enough, laughing and weeping merge into one another. We laugh when we feel like crying and we burst into tears while we laugh.

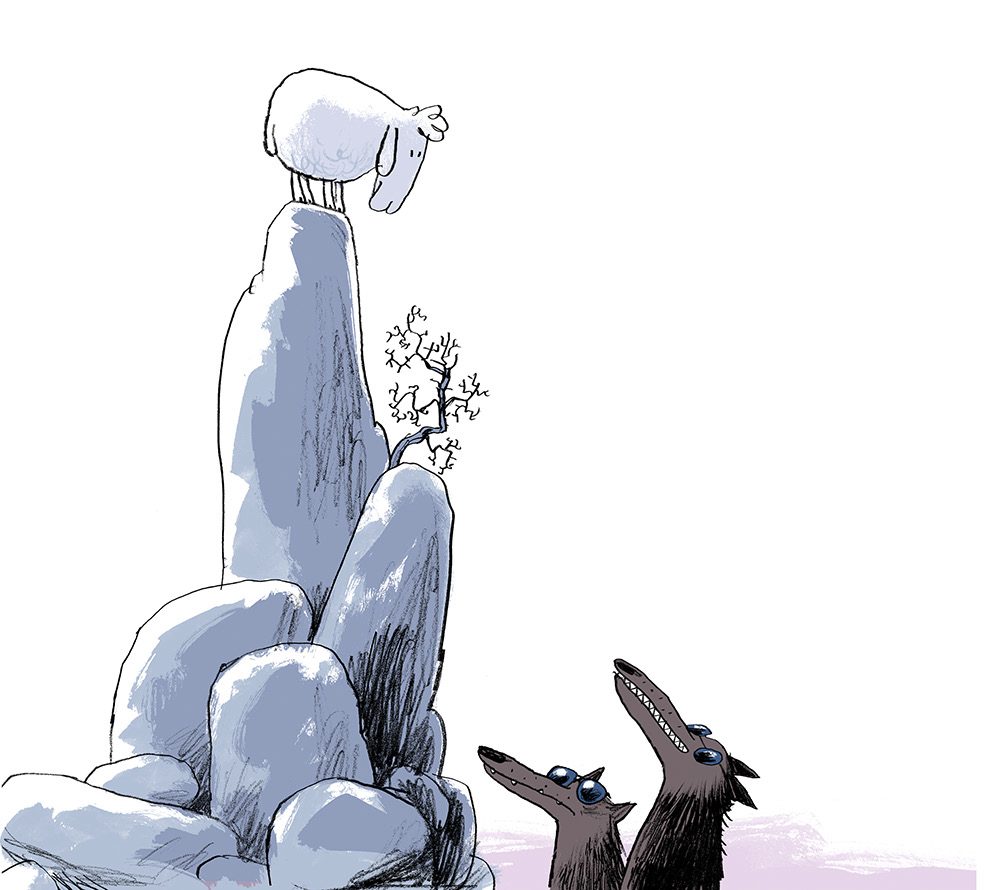

A last word about the last sheep?

The last sheep is obviously an outsider and has no friends. That may well be because its comments are never very constructive—this sheep is a serious curmudgeon. During the story its pride is wounded, so it decides it’s not going to believe in anything other than its own judgement. No wonder the sheep immediately finds itself in a life-threatening situation on a rock with wolves below.

The last sheep seems a bit of a Peter character—Peter, by the way, meaning “rock”. When the sheep feels under pressure, it denies the infant and then betrays it. However, its friends forgive it in the end.

None of the other sheep realize that, thanks to a happy misunderstanding, the last sheep saves the newborn baby. So in retrospect it was critical that one of the sheep left the group. Not least because this one is responsible for the rumour that the sheep were there at the very start. A very successful rumour, as we know today. But that all sounds a bit too conceptual for my liking…

What’s wrong with being conceptual?

A concept always comes to an end—when the story does.

One Wise Sheep | Available October 2024 from all good bookstores

This retelling of the nativity story from the point of view of the sheep is laugh-out-loud funny and full of the warmth of Christmas—a cheeky illustrated chapter book by a bestselling author/illustrator pair.