Adapted from a speech at the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) Australia conference in Sydney February 2019

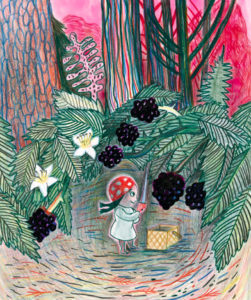

Illustration by Antje Damm, The Visitor

Passion is not a word I love to use – I prefer commitment, enthusiasm, discipline, the ambition to aim for very good, great even, in the books we publish at Gecko Press.

Craft is a lovely word. It includes all of the above, as well as the notion that children’s books are something made.

Writing is a craft, and illustration is a craft. Publishing, translation, design, are all crafts. Talent is of course imperative, but commitment, enthusiasm, discipline – tenacity and determination – are all part of the art and the commerce of producing a good book.

Good books do not appear from nowhere. They may be the result of years of hard work. (Illustrators are not always given years, and that can be hard.)

I have a friend who is a painter. I asked her once: Do you want to be good, very good, or great?

Great, she said.

And who would you consider to be great? I asked. Picasso, she said.

I have never forgotten that, and I’m not sure what I think about it. I think I expected her to say someone in New Zealand, like Ralph Hotere or even Colin McCahon. Her ambition shocked me, but I think it is great.

That was thirty years ago – I must ask her again.

It is good to think about, but not everyone needs to be great like Picasso. I don’t mean for this to sound too lofty. But in writing for children, I like what Madeleine L’Engle said: if it is not good enough for adults, it is not good enough for children. It is wise not to underestimate the intelligence and observational capacity of our audience.

For me, it is enough for a book to be very good, and of course we love the ones that are great.

We don’t know which ones are great until they have been in the world a number of years. It is the connection with readers that makes a book great, in the same way that clothes are not finished until they are worn.

The reader must be at the heart of everything we do.

What makes a good book?

Illustration by Kitty Crowther, Stories of the Night

The making of children’s books has to be one of the most rewarding of careers. We have all chosen a beautiful area of work and probably we are all very nice people.

And yet, what could be harder than writing a strong, imaginative story, where all the pieces are perfectly formed? Or a picture book, where every word must earn its place, humming in tune with the pictures, setting up a much bigger hum, that has children and adults looking, returning, over and over.

At Gecko Press we say that a picture book must work a 70-hour week at least. Writing is hard, illustrating is hard, and publishing is hard. And that is as it should be, in my opinion.

The truth is that there are any number of books in the world and many with beautiful illustrations. But a truly good story is a rarity and the combination of truly good story and truly good illustrations is a magical thing.

The combination of a good book that finds its readers effortlessly is rare and wonderful, and the result of a lot of hard work.

I have heard Kate Wilson, publisher of Nosy Crow in the UK, talk about the five hundred or so decisions that go into publishing a book, and that doesn’t include all the decisions the author and the illustrator, if there is one, have made. There are any number of things that can go wrong.

There are any number of small things that make it go right.

At the core, of course, are the words and for picture books, the special bond between the words and the pictures that set up that constant vibration, a circle of looking and understanding, where the two are greater than their parts.

I think we all know that writing poetry must be hard: picture books are very hard, and hardest of all is a wordless book, where the story must be told with no aids – and sometimes these books require more work from a reader too.

Sometimes these books do not go on to become great commercial successes, and part of our job is to encourage readers and parents to take a chance on a book that requires a little work.

Because just as the craft of making a good book is hard, so too is the work of the reader.

Anything that requires more work of a reader is likely to sell fewer copies, but that in my view does not make it a lesser book.

Illustration by Ole Könnecke, You Can Do It, Bert!

The late John McIntyre, of the Children’s Bookshop in Wellington, used to often tell me that nothing easy is worth doing. He said that if something was easy, then everyone would be doing it – well, quite a lot of people are writing and publishing and illustrating books. It looks easy.

But I celebrate the difficulty of it, because that is what makes it rewarding, the moment when a child’s eyes light up and they point or they giggle, or they go quiet.

Sometimes writers will say that a story ‘just came to them’: but it is not something that happens in isolation, and must be the result of hours and years of thinking about stories, working on them, trying them out, and learning the craft.

Only then can a writer, I believe, harness everything at her disposal to create a perfectly formed story, novel or in the case of the illustrator, a flow of pictures.

There are so many books being published – in my view, too many, though this is not a welcome view, I am sure, among writers.

Constraint is almost always a good thing. I don’t believe that having no restraint or constraint is helpful to creativity. In picture story books, for example, I prefer the 32-page or 40-page at a pinch format, rather than the recent trend for 60 pages or more. I think 32 pages works very well for reading to a child and reading aloud.

In publishing, now more than ever, there is a – not a conflict – but an awareness, of the world of commerce, a pressure for a book to succeed commercially.

Being published is just the beginning, for a writer or illustrator. There is the expectation now that a writer or illustrator will have a ‘following’, be able to speak, entertain, generate noise, for a book to succeed.

There is so much noise, in the world! Increasingly, in fact, I am drawn to stories that celebrate the quiet voice.

I am not a big fan of trying to figure out what the market wants. In my experience, the times we have actively chosen a book because we think commercial have been unsuccessful, and the times we have chosen a book despite it seeming uncommercial have been hugely successful.

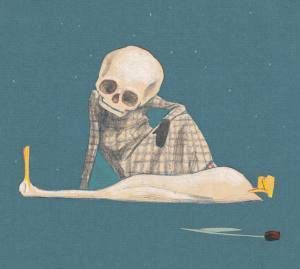

Illustration by Wolf Erlbruch, Duck, Death and the Tulip

New Zealand illustrator Gavin Bishop told me that the benefit, back in the day – when writers and illustrators had to earn a living often through teaching, or working as a postie to finance their work – was that they kept themselves free from market forces. They were writing what they had to write, not what they felt they should write. That must be hard now, as a writer trying to earn a living from their work.

Sometimes the best books come from a risky place where the market was agin.

But you can’t set out to write or publish a risky book. They come from nowhere, and they are risky because they haven’t been done before. For us, these are books that we feel we must, regardless of the niggle that says that they may be unsuccessful commercially.

Hunger Games, Twilight, Duck Death and the Tulip – these are books that had no real predecessors. But there are other books – and That’s Not a Hippopotamus, illustrated by Sarah Davis and written by Juliette MacIver (in my view, a genius book) is one – where we know that there is a strong combination of commercial and good.

What makes a Gecko Press book?

At Gecko Press, we handpick, translate and publish books by some of the best writers and illustrators in the world. We choose books of good heart and strong character, excellent in story, illustration and design, stories children and parents will want to read hundreds of times, for ages 0 to 12 or infinity.

For me, stories of good heart and strong character are ones with an emotional core, even though they may be entertaining, thoughtful, intelligent, surprising – what we call curiously good.

I also like stories to have a beginning, a middle and an end; and an emotional arc.

Gecko Press prides itself on quality production –design, paper, bindings, covers – and on trying to make each book the best it can be, and we are committed to building and maintaining a strong backlist.

This year Gecko Press turns 15 years old – 15 rewarding, tough years.

Gecko Press is small by choice, publishing less than 20 books a year. Of these 20, we publish just a few books of our own: our choice of these books is very personal, as for all our books. Choosing to publish books by some of the best writers and illustrators in the world sets the bar high for our own local publishing: it is very hard to produce a really good book, one that will travel.

Even when we follow an author or illustrator, sometimes it takes years before we find a book we think will cross the border of translation. Not every book by a great writer will make that crossing. And there is the matter of timing…

Golden age

We are in a golden age of picture books, I believe. There are so many wonderful illustrators and writers, and somehow the fright of digital has made publishers want to celebrate the physical beauty of the picture book.

So there are many good books, and many less than good books, all clamouring for attention. In publishing, money and loudness does get you somewhere.

Illustration by Sarah Davis, That’s Not a Hippopotamus

But like Liam, in That’s Not a Hippopotamus, I think it is worth listening to the quiet voice, the observing child, the persistent child.

Gecko Press and other small publishers, and many of you as writers and illustrators, are that child – we are tenacious, persistent, committed and enthusiastic, practising our craft.

We must all try to stay true to our own voice and at the same time, be unafraid to try new things.

There are many good children’s books that celebrate just that.