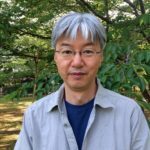

Hiroshi Ito was born in Tokyo, Japan, and graduated from Waseda University with a degree in education. He began creating picture books while still a student and has since published many award-winning books. He had written and illustrated 10 books before creating Free Kid to Good Home in 1991, and has written and illustrated over 90 books since.

Hiroshi Ito was born in Tokyo, Japan, and graduated from Waseda University with a degree in education. He began creating picture books while still a student and has since published many award-winning books. He had written and illustrated 10 books before creating Free Kid to Good Home in 1991, and has written and illustrated over 90 books since.

This book is in its 31st edition. Why do you think it has proven so long lasting?

Free Kid to Good Home is a story about an older sister’s anxiety and dissatisfaction after her brother’s birth. It’s a common theme for a children’s book, but most take the celebratory approach, which asks quite a lot of older siblings, expecting them to be good compliant kids.

This story accepts the older sister’s resentment towards her newborn brother who has stolen her parents’ attention. She feels perfectly justified in thinking, “He’s not even slightly cute,” and sets off to find new happiness on her own. I think many people thinking back to their own childhood will relate to the girl’s actions.

This story accepts the older sister’s resentment towards her newborn brother who has stolen her parents’ attention. She feels perfectly justified in thinking, “He’s not even slightly cute,” and sets off to find new happiness on her own. I think many people thinking back to their own childhood will relate to the girl’s actions.

Emotions like these are important and shouldn’t be dismissed. We need to come to terms with them, just like the girl in this story. Although she doesn’t accept the baby as her brother, she is able to accept him as a “potato”! I think this resonates with many readers.

Adults have also told me that they like the way the parents respond to their daughter, the way they accept her feelings and don’t criticise her actions. This could be another reason the book has endured.

What do you think is important in a good children’s book?

First of all, children’s books need to be good quality literature, just like books for adults. There are technical aspects to writing for children—word choice, clarity—but what’s truly important lies beyond that. A good children’s book has depth, despite its simplicity. The reader should find something new every time they open the book. They will also see different aspects depending on their feelings or situation at that time.

As well as entertaining the reader, they can introduce them to new ideas and challenge their thinking. I also believe that good children’s books should reflect the viewpoints of those who are socially or physically disadvantaged, as well as a core sense of humanity. I feel we must see children’s books as books for everyone.

This story feels very true to the child’s point of view—is it based on real life?

I never write about a real-life experience. Possibly though, some of my childhood memories and experiences influenced Free Kid to Good Home subconsciously. I was the youngest of four siblings and my two older sisters repeatedly told me that I must always obey them because I was a baby orphan abandoned in a cardboard box under a bridge, and if they hadn’t found me, I wouldn’t be alive now. Later in life, I have a memory of seeing my niece, who had been overjoyed at the birth of her baby brother, looking down at him while he was sleeping with eyes so cold it was frightening.

My son loved his younger sister very much and took good care of her, but even so he once came down with hives that covered his body, most likely due to stress. This happened years after I published the book, but it most likely influenced the Free Kid to Good Home sequels.

My son loved his younger sister very much and took good care of her, but even so he once came down with hives that covered his body, most likely due to stress. This happened years after I published the book, but it most likely influenced the Free Kid to Good Home sequels.

When writing from a child’s point of view, I pull on my own childhood memories and listen to the child in my heart. It might not be the same life as a child of today, but as long as the character is consistent and can convince the reader, that’s good enough for me.

How do you add humour to your illustrations?

Humour is most important to me. It’s a means of survival. Some issues feel so huge they can crush you if you confront them head on, but humour helps us approach problems from a different angle. It helps reduce them to a manageable size, even if we can’t completely solve them. I think that naturally comes through in my illustrations.

Children’s book illustrations have their own value for me, distinct from conventional art. I aim for illustrations that might not look special at first glance but invite a closer look—maybe like an illustration on a candy wrapper or a sloppy doodle that makes kids think, “I can draw better than that.” They won’t be considered “amazing” by conventional standards, but precisely because of that, they don’t make people tense. I want to use this type of art as a means to make myself and other people happy.

What is your experience of learning to write and draw?

What is your experience of learning to write and draw?

I didn’t study art at school, nor did I ever have a professional teacher, but I belonged to a Children’s Book Research Club during my university years. We all loved picture books, discussed their history and characteristics, and began making our own. We were self-taught. Learning how to illustrate was the same—I learned how to do it by just doing it.

Fortunately, during these early years, I found wonderful picture books that I still consider to be my mentors. If I were to call anyone my teacher, it would be the many excellent children’s books I have read.

Free Kid to Good Home is available from all good bookstores and our website.